The Other Side of Inefficient Fertilizer

Over the past year, Growers has focused a lot on cost and nutrient availability analysis for different fertilizers and fertilizer programs. An important aspect of this is the efficiency of different types of fertility, including but not limited to liquid or dry products, placement location, and raw ingredient quality. As our focus has been on showcasing the actual amount of nutrients being used by the plant, we haven't looked very much at those nutrients being lost as a result of being unavailable to the plant. This article will attempt to explain why those are just as important a discussion topic as availability to the plant.

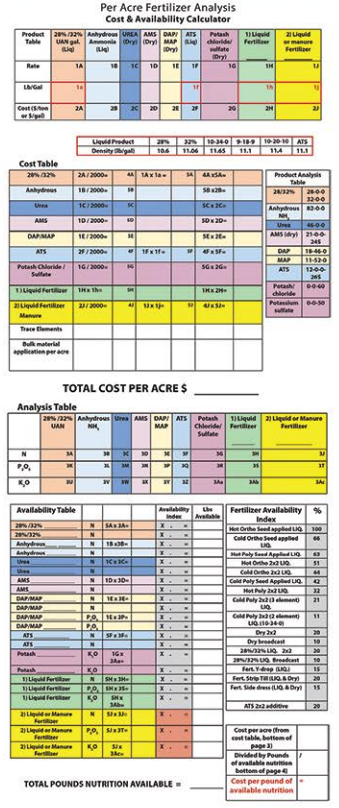

The vast majority of fertilizers are not entirely available to a plant. There are numerous reasons for this, some of which are listed above. But suffice it to say that the assumption that you are benefiting from all of the nutrients in most products in false. This should certainly bring into question what you are getting for your investment (the original purpose of our cost and nutrient availability calculator seen at right), but given the detrimental environmental effect of lost nutrients, your concern should expand there as well.

Let's take a quick look at a 200-pound broadcast application rate of a dry fertilizer. According to both a study out of Michigan State and a multi-university study based at Kansas State, broadcast dry fertilizers are only 10% available to a plant. This means that of that 200-pound application, 180 of those pounds is not being used by the plant. Some will try to make the argument that you are "banking" those nutrients in the soil for later, but there are a couple of problems with that logic that I would like to focus on. The first is that, because of decades of overfertilization, most agricultural soil is already at its saturation point for nutrients. Like a sponge that is already soaked with water, any additional nutrients will be easily lost from the soil colloids. The second is that many nutrients rely on soil microbial life to convert those nutrients into stable forms that will stay in the soil. Many fertilization practices actually harm healthy soil microbe populations, including the use of impure fertilizer, thereby also damaging their ability to convert said nutrients. For those two reasons alone, it is overly optimistic to think those remaining 180 pounds of nutrient are being held in the soil.

How are those nutrients then lost, and what happens to them once they leave the field? If a nutrient is not absorbed by the plant or converted into a stable form by microbes, the only pathway left for it to take is to be washed away, either by solubilization or erosion. Therefore, nutrients can be lost through either surface runoff or through tile drainage. Once in a waterway, they will eventually be used by aquatic plant life, potentially leading to eutrophication, algae blooms, anoxic zones, and a host of other problems associated with nutrient pollution. The solution does not lay with top-down regulation to try to prevent those nutrients from leaving the field but rather with the individual making wise fertilization decisions.

The purpose of this article is to draw your attention to not only being as efficient as possible for your own operation's sake, but also to be aware that your practices have downstream effects for you and many other people. Don't just look at the 10% that a plant is using, but also at the 90% it is not.

This is an excerpt from the Spring Growers Solution (2021) written by Zach Smith.

Signup for our newsletter to stay in the loop